Stacy Pearsall's office is tucked away in an upstairs bedroom of her Charleston area home. Her service dog Charlie checks in occasionally, tail wagging, making sure she's alright. Above her desk, hangs a collection of spoons; small, some silver, simple and ornate. Stacy says she handpicked them for a loved one during her travels overseas, someone who has since passed away. They reflect her love of service and a discerning eye.

The 38 year-old is a photographer, a master of the moment and light. Her story is as complex as the portraits of veterans she takes. “I see people differently,” she says. It shows.

Elizabeth Barker Johnson poses in large, antique chair with delicately carved handles. A petite woman, she clasps a 1943 Army photo of herself. The expression on her face is unchanged, a knowing smile. “In my opinion she is even more beautiful,” says Stacy. “Every wrinkle on that face she earned heartily and I respect her for what she went through.” Stacy explains she served as a postal clerk during World War II in all African American unit. “We’ve come a long from when she served.”

Stacy Pearsall joined the military when she was 17 years-old, like many of the men in her family had done before. She served as a combat photographer with the U.S. Air Force in Iraq. Veteran Bobby Henline was there too, serving in the same province at the same time. Only she didn’t know it, until she photographed him years later.

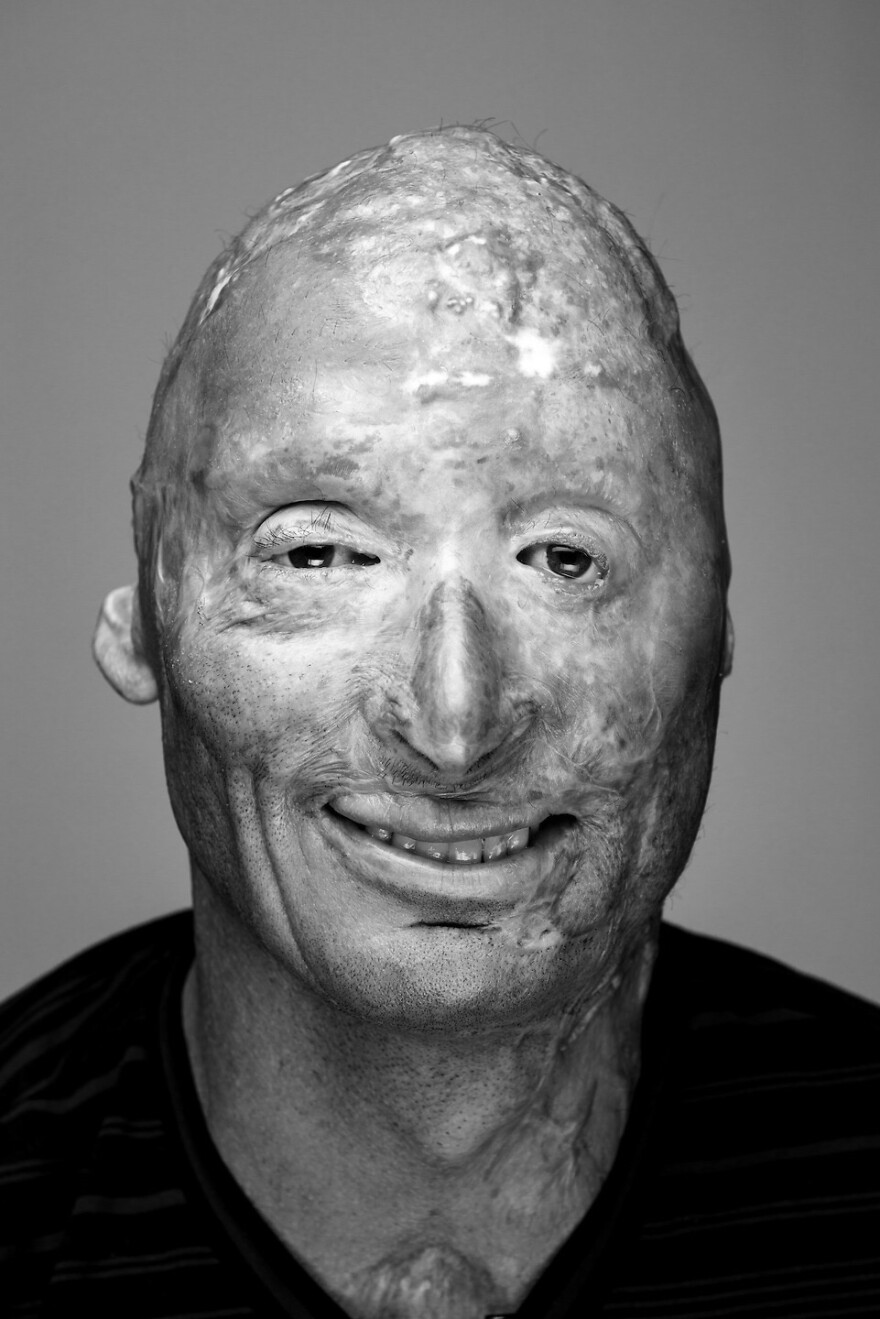

“Where some people may see only his burn scars, I see his life lines and his laughter wrinkles and the curve of his mouth, and the joy that comes through his eyes.”

Bobby, she explains, was the only survivor in a fight that left him badly burned. They were even in the same hospital at the same time from different battles; again she didn’t know, perhaps separated by their own pain.

“His personality hasn’t changed,” she says. “He’s still there.” “For me, this portrait expresses the totality of his story and the measure of his sacrifice for our country.”

Stacy joined the military at a time when women were not allowed in combat, yet she found herself immersed in it as a combat photographer capturing conflict. "It was routine to hear gunfire. It was routine to hear screaming," she says. "My job was to photograph war, so I needed to get over the fear of dying to embrace my job."

She also needed to learn when to put down the camera and pick up a gun. It's a choice she had to make on several occasions. She recalls one. "It was a mess. Essentially we were funneled into a kill zone and we were ambushed. There were enemy all along the roof tops and they were just firing down on us like ducks in a pond."

Stacy was injured several times. But the last blow, she says, was one she could not recover from. Trauma to her brain and spine ended her military career. She was crushed. This was her life. She even considered suicide.

“I spent a lot of time circling the drain,” she says. “By that I mean I spent a lot of time thinking about the what I could have done or should have done and lost friends.”

She was in a VA hospital fed up and tired, when she says an elderly man sitting next to her began to stare. “My kettle was whistling,” she says. “I was about to give him a piece of my mind.” But slowly the aperture of her inner camera opened, letting in just enough light.

“That was the moment he was waiting to spill his own life story,” she says. He was missing a finger. A recruiter initially turned him away. He later survived Normandy, got captured as a prisoner of war and helped liberate a concentration camp. “This guy was a World War II greatest generation hero.”

From that day forward, Stacy began bringing her camera to medical appointments and as she says, the Veterans Portrait Project was born. http://www.veteransportraitproject.com/ It’s been 10 years and Stacy has photographed some 7,000 faces. Her goal is to take pictures of veterans from every state and province where the Department of Defense recruits. So far she’s been to 29 states.

But perhaps her most profound portrait personally is that of an Army widow. Shelee Murray lost her husband in 2011 in Afghanistan. It’s a loss Stacy simply can’t imagine, but has seen firsthand.

“As a combat photographer, I had to photograph some really tough things and that includes the last part of someone’s life.”

She says her friendship with Shelee, photographed with her late husband’s dog tags, has only deepened her mission to live outside herself and serve others.

“All I ever wanted to do was to honor their memories and the project is a way for me to do that. I’m going to live the best life that I can because they can’t”